|

| Violet Jessop, Stewardess |

Birth Name: Violet Constance Jessop

Born: October 2, 1887 in Argentina

Occupation: Ocean liner stewardess

Marriage: October 29, 1923, John James Lewis, divorced - no children

Died: May 5, 1971, age 83 in Suffolk, England

Violet was the oldest of nine children born to an Argentinian sheep farmer and his wife. Six children survived childhood. When she was five, Violet became ill with tuberculosis and her parents were told her condition was fatal. They were devastated because they had already lost three children to childhood illnesses. However, Violet got well. She continued going to school and after school, she helped her mother take care of her younger siblings.

In 1903, when Violet was sixteen years old, her father died from surgical complications. Things were about to change for the worse for Violet's mother because she was left with six children to raise and no job prospects.

In 1904, she moved her children from Argentina to England where she hoped to find better employment opportunities. After searching for a month or more, she got a job working as a stewardess on passenger ships which paid £2 per month. The job meant she would be at sea for up to seven days at a time. As the oldest child, Violet was expected to care of her siblings while her mother worked.

In late 1907, her mother became ill and had to leave her job. Violet said she would go to work while her mother stayed home with the children.

Violet reluctantly applied to the shipping companies but not White Star because she heard the rich people were hard to please, their North Atlantic voyages didn't appeal to her either. She applied to other shipping companies but no one offered her a job.

|

| Colorized portrait of Violet Jessop |

Her mother thought Violet's beautiful Irish appearance might be the reason she wasn't getting hired. She suggested to Violet that maybe the shipping companies were concerned about hiring her because she was too pretty. If she changed her appearance to make herself less attractive, she might get hired.

That did the trick. The Royal Mail Line hired her as a stewardess and her first assignment was on their ship, the Orinoco.

The duties of a stewardess were different in each department on a ship:

- if assigned to the galley or kitchen, a galley steward may be a dishwasher, cook, baker, chef, or as a food server in any of the dining rooms, the ala carte restaurant, the buffet and room service.

- if assigned to the ship's laundry, this stewardess would perform laundress duties to deliver trolleys of linens several times per day to each station to keep all stewards and stewardesses supplied with clean linens for their assigned staterooms. Some laundry stewards were assigned to the swimming pool which was open on a schedule.

- if assigned as a cabin stewardess, each passenger class had their own stewards and stewardesses who would tidy staterooms several times per day, deliver a supply of clean towels and linens, answer summons to cabins, and turn down beds at night. This position assigned from 5 to 25 rooms per employee depending on the class assignment and often earned more in tips than they did in salary.

- as a personal maid and/or governess to one or more cabins for a voyage.

At Royal Mail Line, Violet was paid £1. 10s per month, a fraction of what the male stewards were paid to work the same 18 hour days. She stayed at the Royal Mail Line until early 1911, then started looking for a job that paid more money and had a better work schedule so she could have a social life. As much as she didn't want to, she reluctantly applied to The White Star Line and they hired her as a stewardess. At the time, White Star Line did not assign an employee to work steadily on one ship. They worked on all 29 steamers so her assignment was changed weekly.

Violet and other stewardesses worked 17 hour days and were paid £2, 10 shillings per month or a little bit more than £24 per year. ($32.00)

In today's dollars, one British pound equals $1.28 US dollars. This link will take you to the website to convert British pounds to US dollars. I have the converter set at £2 but you can change the number of pounds. Play around with it so you can see how much the crew actually earned.

Keep in mind the results you see show the value of money on the day you are using the link, not the year 1912. I couldn't find a link that gave a conversion adjusted for inflation from 1912 to today's date.

See links at end of this post for more about crew salaries.

RMS Olympic

In May 1911, Violet's assignment was changed to White Star Line's newest ship, the RMS Olympic, which was said to be the largest and most luxurious ocean liner in the world, surpassing those of their main competition, The Cunard Line. Violet was told she would stay on this ship as a permanent assignment. Her salary increased to £3. 10 shillings per month.

Captain Edward J. Smith was the Captain of the Olympic for her maiden voyage.

- In 1904, Captain Smith had received a promotion which, in part, said he would be assigned command for the maiden voyage of every new ship for the White Star Line. He became very popular with the passengers.

On June 14, 1911, Violet was aboard the Olympic for her maiden voyage. The Olympic sailed from Southampton, England, then picked up passengers at Cherbourg, France and on to Queenstown, Ireland before setting sail for New York City.

Ten months later, this would be the same itinerary for the RMS Titanic.

A week later, the Olympic arrived in New York City on June 21, 1911 with much fanfare. The ship's designer Thomas Andrews was aboard, as was J. Bruce Ismay, director of White Star Line who owned the Olympic. It was this trip when Thomas Andrews began his practice to go on the maiden voyage of all the ships he designed.

Once they docked in New York, the RMS Olympic attracted immense attention from the press.

Giving in to the public's curiosity, J. Bruce Ismay told Captain Smith to open the ship to the public for a few hours. All ship officers were to be in dress whites. Ismay thought this would be good to drum up future business. Besides the ship's doctor, J. Bruce Ismay was the only person on board who could give orders to the Captain which he had to obey.

8,000 numbered tickets were hastily prepared and distributed for free to visitors to go aboard for a short tour. Before leaving the ship, the tickets were collected to make sure everyone was off the ship. Even though they only printed 8,000 tickets, the newspapers reported that more than 10,000 people boarded RMS Olympic for a tour and they said double that amount watched her leave New York to return to Southampton.

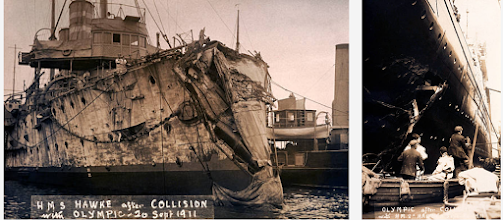

On September 20, 1911, Violet was on the RMS Olympic for its fifth voyage when there was a bit of trouble.

The Olympic and the British warship HMS Hawke were moving parallel while going through the Solent (a body of water that separates the Isle of Wight from mainland England). Suddenly Captain Edward Smith ordered the Olympic to turn to starboard and in doing so, the ship's turn went very wide causing big swells.

This maneuver took the HMS Hawke's Captain by surprise because, as he said later, there was little or no reaction time to avoid impact. The Hawke was sucked so close to the Olympic that the Hawke nearly capsized.

|

| (left) HMS Hawke, (right) RMS Olympic |

As a warship, HMS Hawke's steel-enforced bow was designed to sink ships by ramming them. The Hawke's bow tore a 40 foot gash in Olympic's hull which extended both above and below the waterline. One of the Olympic's propellers became twisted which rendered it inactive, and two of watertight compartments were flooded.

|

| Damage to RMS Olympic |

No one died and neither ship sank, but the HMS Hawke suffered very severe damage from contact with the Olympic. The Hawke had to be towed and was out of commission for nearly six weeks. It wasn't scrapped; both ships were repaired and returned to service.

An official investigation by the Board of Inquiry was conducted to determine fault and the cause of the collision.

Thomas Andrews, J.Bruce Ismay, three future Titanic crew members and stewardess Violet Jessop were aboard at the time of the Olympic's collision with HMS Hawke. They would also be on the Titanic when she sailed on her maiden voyage.

Each one was called to testify at the Board of Inquiry hearing. The White Star blamed the RMS Hawke for coming too close and the RMS Hawke blamed Edward Smith for causing the collision by his abrupt wide turn which created a suction that pulled the Hawke closer to Olympic's side. After hearing all the testimony, the Board of Inquiry deliberated and their conclusion was they agreed with the RMS Hawke.

The Olympic was out of service for eight weeks and all scheduled voyages had to be canceled, which financially devastated the White Star Line. Some employees were moved to other ships, but Violet got some welcomed time off.

The HMS Hawke did not stay in service much longer after this incident because in October 1914, it was sunk by a German U-boat.

After RMS Olympic's Collision

After the Olympic's collision, Violet Jessop was chided for staying with the company after the accident because, they said, it might have made a more timid victim swear off ever sailing on another ocean liner.

Around 1971, Violet Jessop wrote her memoir. Then for some reason, she put it away and didn't finish it. The material was discovered in 1985 and her family had it published in 1997. The incident with the RMS Olympic was one that she would not talk about in any newspaper interviews, nor did she discuss it in her book.

Violet was happy on the Olympic so when she was told she was being transferred to the Titanic, she considered quitting White Star. But her friends told her she would be missing out on a great experience. So she agreed to transfer to the Titanic crew.

RMS Titanic

On April 10, 1912, twenty-four year old Violet was employed in First-Class on the White Star Line's newest ship, the RMS Titanic. Her salary was £3, 10 shillings per month.

|

| RMS Titanic |

She mentioned Thomas Andrews in her memoirs several times and was especially enamored with him. He was the only person who asked for (and received) constructive suggestions from the crew on how to improve the crew's quarters on the Olympic. On the Titanic, they were already very comfortable. He asked opinions of crew work areas and public rooms.

"Often during our rounds, we came upon our beloved designer going about with a tired face but a satisfied air. He never failed to stop for a cheerful word, his only regret that we were getting further from home. We knew the love he had for his home in Ireland and we suspected he wanted to get back home for a much needed rest and to put aside the business of dealing with ships."

In her book, Violet wrote that she received at least four marriage proposals during Titanic's maiden voyage.

Violet became friends with Jock Hume, a Scottish violinist who was a member of the orchestra. She said it was her routine to take in fresh air on deck before retiring for the night and he often walked with her when he wasn't working. She brought a copy of a translated Hebrew prayer book that an Irish passenger had given her a few years ago. Violet was a devout Catholic who kept a rosary in her apron pocket at all times and prayed throughout the day. She read the Hebrew translation every night before going to bed and it was while she was drifting off at 11:40pm that Titanic hit an iceberg.

Violet talked about this experience in her memoir, 'Titanic Survivor' by Violet Jessop and John Graham.

"No one said we hit an iceberg. No one ever said how bad the damage was. We were made to think this was not a devastating blow."

"Nearly an hour later, I was ordered to go up on deck. Once there, they were working on getting lifeboats ready. All I saw was calm, passengers strolled about, congregated in small groups. When the officer said it was time to get in lifeboats, I was told to stand at the bulkhead with other stewardesses. Then I saw women cling to their husbands, tearfully saying goodbye before being put into the boats with their children.

"There were some women who didn't speak English and refused to get in the lifeboats. We were ordered to get into lifeboat 16 to demonstrate that it was safe, show them how to board from the deck, and how to not be afraid to get into the lifeboat."

A while later, she and the other stewardesses were still standing nearby watching lifeboats being filled.

"I saw that there was only one wooden lifeboat left and mentioned it to the officer. Then at 1:30am, two other stewardesses and I were told to get in Lifeboat #16.

"As the boat was about to be lowered, one of the officers handed me a baby, saying it had been separated from its mother. I looked after the baby, shielding him and myself from the cold weather in the lifeboat. I watched what was left of Titanic graciously sink below the water, and then sat to wait until we were rescued ten hours later by the RMS Carpathia. Still clutching the baby once we were aboard the Carpathia, a woman grabbed the baby right out of my arms, then ran off without saying anything to me. I had no idea whether the woman was the child's mother but for the rest of the three days on the Carpathia, I never saw the woman or the child again."

(Note: It is interesting how some survivors perceived time. Although being adrift on the ocean can seem like days instead of hours, there were several accounts who said they were in the lifeboat for 10 hours, and others said that it was 8 hours. Actually, it was less than 5 hours because the Carpathia's timeline and activities were very well documented. The stewardesses were put in Lifeboat 16 around 1:30am, the Carpathia started picking up survivors at 4am. Violet's lifeboat was the third one located in the water and was brought onboard Carpathia at 5:00am. That was three and one half hours.

The last lifeboat of survivors was brought onto the ship at 8am, and by 8:30am, the Carpathia was setting a course for New York City. The longest anyone was adrift in their lifeboat would be less than 8 hours.)

Violet helped with caring for Titanic's survivors for the next three days while the Carpathia journeyed to New York. When she recovered from her experience on Titanic, she testified before the Board of Inquiry and went back to work at the White Star Line in late 1912.

HMHS Britannic

When the First World War broke out in July 1914, Violet Jessop volunteered for the British Red Cross on their hospital ships.

In November 1916, the British Red Cross began to use ocean liners as hospital ships. The Britannic was put into service as a hospital ship.

|

| HMHS Britannic as hospital ship in WWI |

Violet had survived a collision on White Star's Olympic with the HMS Hawke, and the sinking of White Star's Titanic. On November 21, 1916, she found herself on the Britannic, now a hospital ship when it struck a deep sea mine.

This time they didn't have two hours before the ship sank. It only took 55 minutes. There were 1066 people on board and 30 died. At the time, there were all kinds of stories circulating that Britannic had been hit by a torpedo or the Germans had planted a deep sea mine. Some even thought that White Star sunk their own ship.

After the crew was put in lifeboats with passengers, they were nearly killed when the lifeboats got sucked in by the ship's propellers. Violet jumped out of her lifeboat to save herself and suffered a traumatic head injury that caused her to have headaches for years.

"I leaped into the water but I was sucked under the ship's keel and struck my head. I escaped, but years later when I went to my doctor because of a lot of headaches, he discovered that I had sustained a skull fracture."

Two other Titanic survivors, Arthur John Priest and Archie Jewell, were also on board Britannic and survived.

In 1920, Violet returned to work and changed employers to Red Star Line and by the early 1930's she was back at Royal Mail Line again. She enjoyed going on around the world cruises twice on the Red Star Line's Belgenland, which had previously served in World War One, then was heavily overhauled to become a very comfortable luxury ship.

Marriage

On October 29, 1923, thirty-six year old Violet married ship steward John James Lewis, age 46, from Southampton. With her biological clock ticking and nearing 40, she wanted to have a family.

In 1923 when they were both working on the Majestic, the ship had no scheduled voyages for two weeks. The crew was paid off and released in Southampton. Violet and John went to London and got married four days later with very little fanfare. She had time to contact her Aunt Sadie and Uncle Cecil Ridley with whom her mother and siblings lived after moving from Argentina. Her Uncle Cecil gave her away and was a witness on their marriage certificate. Afterward, they went out for a wedding breakfast, then left for a short honeymoon in London. By the middle of November, John and Violet Lewis were back to work.

After one year of marriage, they agreed to separate with no financial agreements between them. John Lewis died in 1959 at age 83. Violet and John had no contact after their divorce.

Up until 1997 when Violet's memoirs were published, nothing about her husband was known. She wrote that she was disappointed very quickly in her choice of husband and they separated after a year. She said she always held the dream that should would marry a rich first-class passenger.

She described the marriage as "brief and disastrous," lacking fellowship and sympathy. Her new husband seemed not to be who he purported to be and that might have led to the early demise of the marriage.

In 1950, Violet Jessop retired to a 16th century thatched cottage in Great Ashfield, Suffolk, surrounded with mementoes of her 42 years at sea.

In 1958 she was interviewed when the film A Night To Remember was released and in April 1958 joined other survivors for a dinner in London to mark the 46th anniversary of the sinking of Titanic. The other crew members were Lawrence Beesley, Marjorie Collyer Dutton and Gus Cohen attended.

Violet Jessop died on May 5, 1971 of congestive heart failure at the age of 83.

Interesting Reading

Collision of RMS Olympic vs HMS Hawke

And The Band Played On (Jock Hume Story)

You are here:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for your comment